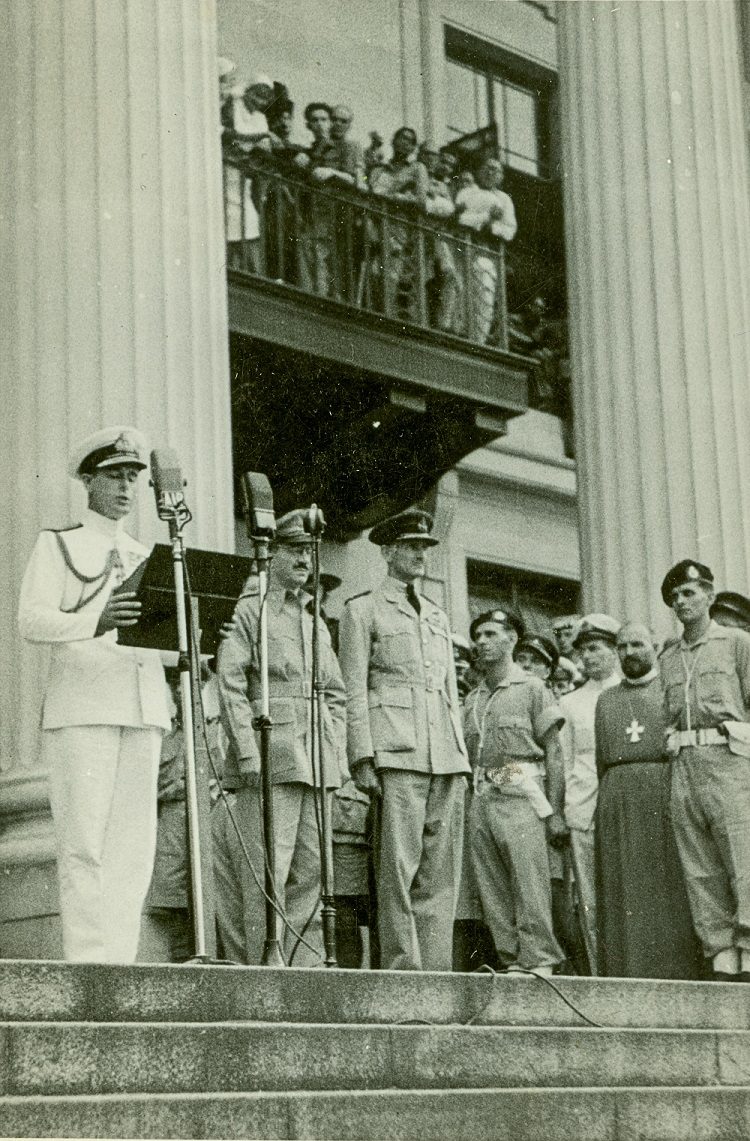

For many of Bexhill’s late residents, the end of the war in Japan – marked as VJ Day on 15 August 1945 – was a watershed moment in all their lives. Moments of daring on the ground as their Japanese captors faded away, and relief for those at home, many hearing of the fate of their family members for the first time in three years.

For Reginald ‘Tim’ Hemmings of Bexhill, it meant commandeering a Japanese train with a group of fellow POWs to get to the coast to meet newly arriving US forces. To George Kent of Maberly Road, Bexhill and Thomas Kennard of North Road, Sidley, it meant a precious telegram to both fathers, confirming that their sons were alive and coming home.

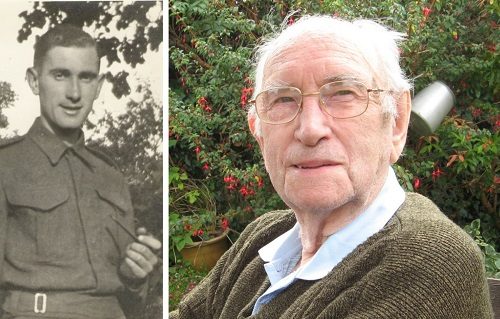

Captured when Singapore fell in February 1942, Tim Hemmings was first interned at Changi and later sent to work on the Burma Railway — one of the most notorious forced labour projects of the Second World War. For more than three years he endured malnutrition, disease, and brutal treatment.

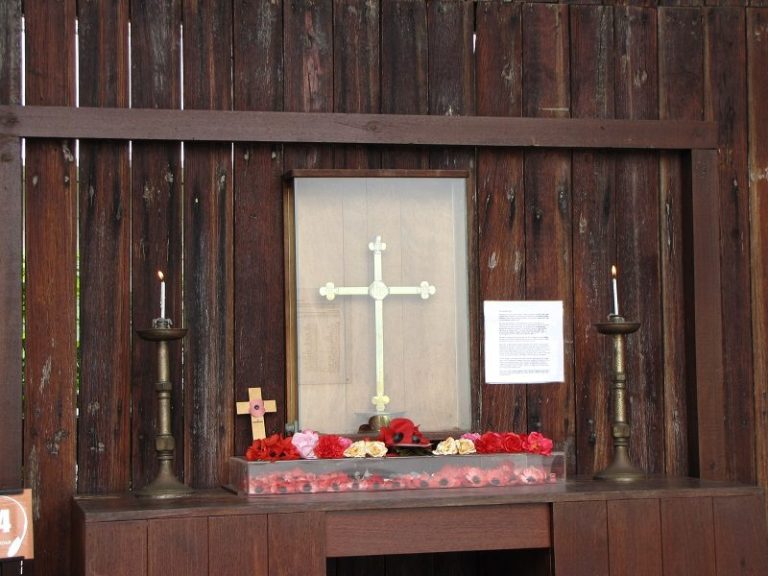

Days were spent in backbreaking labour under sweltering heat, sustained by thin rice gruel and scraps of vegetables. He improvised tools and even carved wooden grave markers from scavenged materials for fallen comrades. A cross he made while in captivity using only a metal umbrella spoke, pictured above, is on display at the Changi Jail museum in Thailand.

These stories were documented at the time by the Bexhill Observer, both at the time in 1945, but also years later, after long periods when the survivors found it hard if not impossible to relate their experiences to others.

One who did, the brother of Colonel Arnold Shelton Agar DSO, of Bexhill, wrote of his experience in a letter shared with the Observer a few months after the end of the war. As a civilian internee in Singapore’s Sime Road Camp, he described three and a half years of systematic starvation, appalling living conditions, and deliberate humiliation.

Prisoners were crammed into overcrowded cells, denied clothing and equipment, and left to improvise cooking pots and utensils. Visits from the Red Cross were blocked, letters censored and delayed, and minor infractions met with beatings.

Other Bexhillians did not survive the experience: Captain Alexander Charles Dallas-Smith MC of the Gurkha Rifles died in captivity in March 1942; RAMC Private John Morley died days before the end of the war, on 20 July 1945 in Changi jail; Royal Engineer Lieutenant Andrew Murdoch, grandson of Albert Road doctor Albert Murdoch, died of wounds in captivity in February 1945; Gunner William Saunders died of vitamin deficiency in February 1942 at 4D camp in Thailand; Private Roland Thomas of Hillside Road, Bexhill, died of diphtheria aged 21 in November 1942; Private Adrian Winbourne died working on the Burma Railway; Lieutenant Robert Woodhead of Holmesdale Road, Bexhill, captured at Singapore and shipped as slave labour to a remote island, later murdered in a mass execution in June 1943.

For the survivors, their stories converge on the same moment: the war’s end and the prospect of freedom. Tim’s thoughts turned to Thelma, the young woman he had met in 1941 and not seen since; she had waited over four years for his return. Colonel Agar’s brother dreamed of bread, meat, and a pint of beer — simple pleasures that had taken on the weight of symbols.

Looking back, both accounts reveal an extraordinary mental adjustment: not only surviving deprivation, but re-learning how to think about the future. Colonel Agar’s brother imagined telling his story one day with a touch of wry humour, recalling how even snails and rubber seeds had been turned into food.

Tim, who rarely spoke of his experiences for decades, eventually shared them so that younger generations would understand both the suffering and the resilience. He agreed to share them with his son, also called Tim and daughter-in-law Sally Hemmings, for Bexhill Museum, a book and a short film.

Their voices, preserved in film and in print, capture the moment when the gates opened, and years of endurance gave way to cautious joy — the first steps from captivity back into life, and the long process of coming to terms with memories that would never fade, but no longer had the power to define them.

Details of British soldiers from Bexhill or with Bexhill family connections from the online Bexhill-on-Sea Roll of Honour.