Every museum has its mystery objects. Items of obvious beauty or other value that have come without the historic records needed to make full sense of it – its ‘provenance’. Who made it, loved it, parted with it, and how it came to be in our care in the first place.

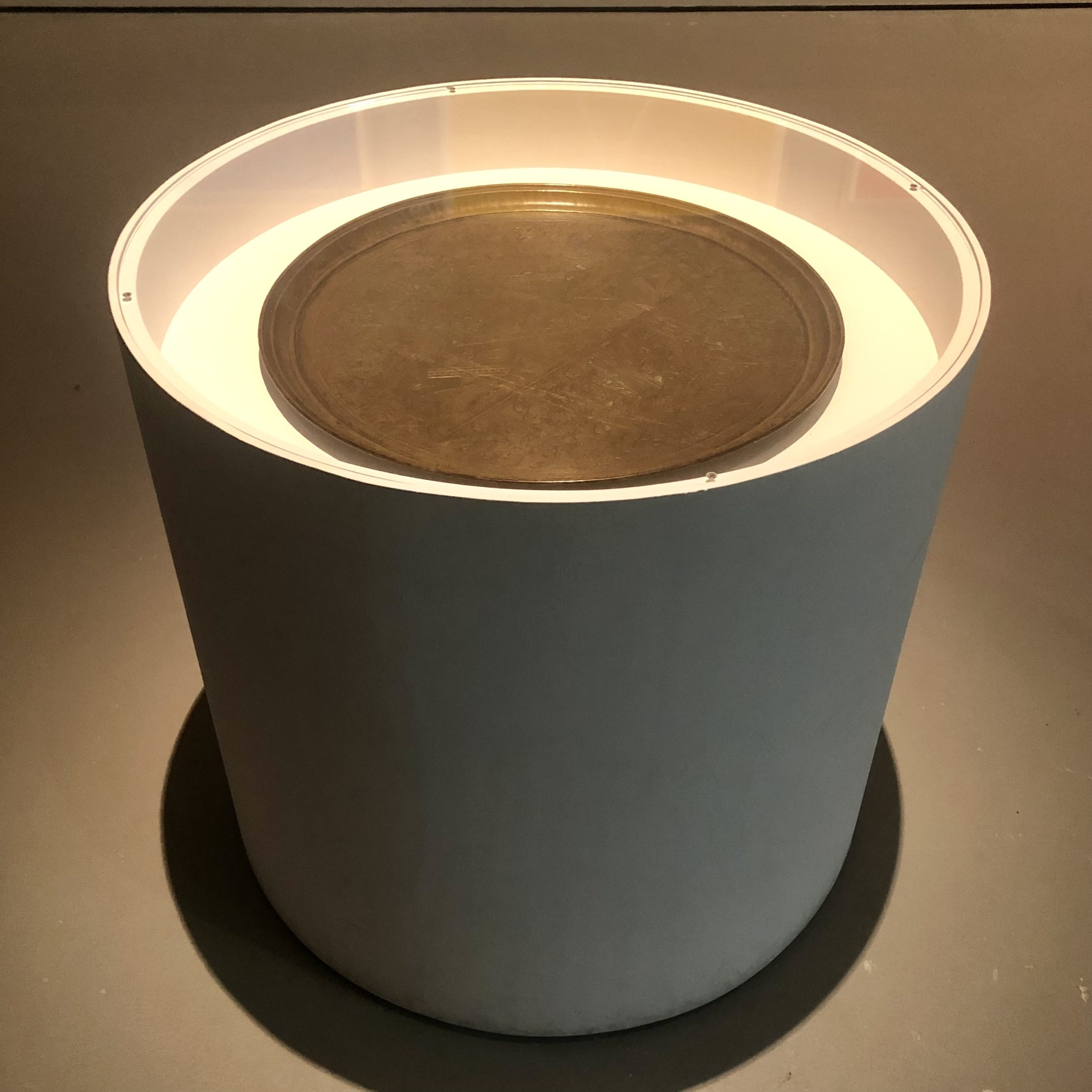

The grandest and humblest institutions all have their share of such obscure artefacts, including Bexhill Museum, and the Victoria & Albert Museum in London is no exception. So, from the V&A stores comes a rarely seen circular brass tray, made on the banks of Iraq’s Euphrates River in 1918. Little is known about it, other than it was donated by a ‘Mr Bing’ and that the V&A had given it the ‘lost number’ 310. The tray itself is inscribed around the edges in colloquial Arabic, giving a date and a place of both its manufacture and the events it illustrates. This spring it was taken out of its box and placed in the care of Iraqi-born artist Jananne Al-Ani and our neighbours at Eastbourne’s Towner Gallery.

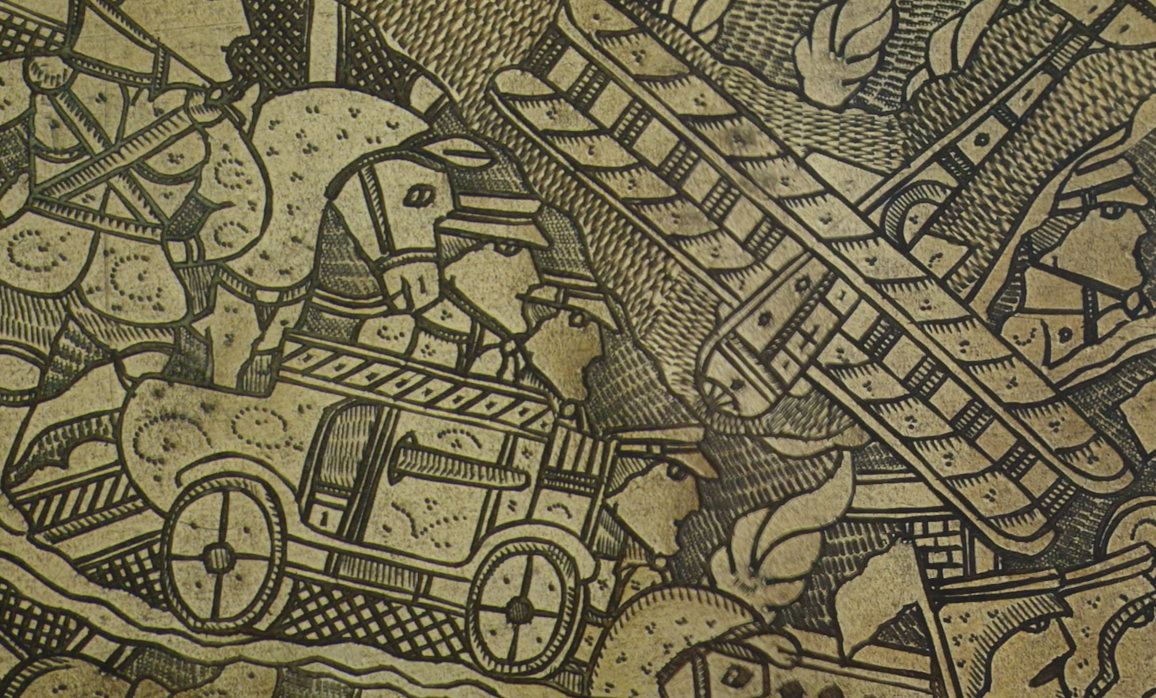

They have done a marvellous job in bringing digital technology to bear on its reinterpretation and display. The 58cm wide tray pictures the Iraqi town of al-Hindiyyah on the River Euphrates, in 1918 literally filled to the brim with British soldiers and their kit, artillery, vehicles, rifles and overhead, two biplanes from the then newly founded Royal Air Force. Al-Ani used ultra-high resolution digital cameras to get up close and personal images of each of the tiny-embossed half centimetre high figures that pack the plate’s surface. She then used the results to make an extraordinary panoramic film display for the Towner.

Images of individual British & Empire troops in soft desert caps and solar topees are stamped into the brass, distinguished by their identical pointy chins and noses, hands on hips in decisive poses. Filmed down to the micro-millimetre and then projected in 8K digital detail across an entire wall of the Towner, the effect of light on brass and the precision of the original craftsmanship transforms the object’s story into something more meaningful, yet still mysterious. As the Towner fairly describes, Al-Ani – of mixed Irish & Iraqi heritage – “reveals a micro landscape within the surface of a museum object and employs testimony and storytelling to reflect on the relationship between Britain and Iraq”. The soundtrack draws upon interviews with her mother, recalling personal experiences of growing up in Britain as the child of Irish immigrants and living in Iraq through intense social and political change.

Indeed Al-Ani has done something quite special with the object and her off-the-shelf open-source digital tools. Digital technology’s engagement with, well, everything, tends to be acquisitive, based on its business model of ownership, redefinition & representation on its own terms and conditions. In that there’s a parallel with the museum and gallery world and its occasional taste for collection and ownership over sharing and interpretation. Academics theorise a digital condition of hybridity, a new and discrete space that is the technologist’s own to hold, rather like the way the museum or gallery might lock away its treasures, or an imperial force might hold a country, on the grounds that because it can, so it should.

With the proactive support of the Victoria & Albert Museum, Al-Ani takes the artefact out of this space, figuratively liberating it both from the store and the constraints of digital reproduction. The connections between her and the original unknown craftsman, both cultural and creative, are preserved. It adds a fresh ‘post-Benjamin’ aura of authenticity and authority to the work, placed on a par with the digital, enabled by it, not subordinated to it. (In a lovely coda, an old-fashioned magazine article about her work led the owner of a near-identical Iraqi brass tray to contact the gallery. Their example came with the museum world’s most resolutely analogue and precious data form, a handwritten letter from the original owner giving up its history and provenance.)

The technology serves both Al-Ani and the unknown craftsman well at both ends of their shared timespan. The camera bears down on the beautiful embossed brass, and where even the tiniest cameras cannot be physically turned to follow the engraving’s channels, an amazing animated sequence is added where the grooves in the plate are transformed into winding desert wadis, dried riverbeds, before rising up to frame a bronzed image that mimics the twin rivers that define Iraq, history’s foundational Fertile Crescent, home of the Garden of Eden, and the birthplace of civilisation as we recognise it today.

Back to the plate, civilians are illustrated moving amidst the throngs of troops, veiled women and softer faced Arab men with aquiline noses and shemaghs on their heads, in contrast to the angular Brits and their own militarised versions of tribal headgear. Some Arabs are pictured crossing the river, possibly returning townsfolk waving white flags. For this is not a celebration. This is a record of British victory.

The V&A’s guess was that the tray was made to commemorate Armistice Day 1918. It appears to be something more subversive. In prime position, the image of a condemned man being hung for the crime of murdering a British officer, his name on the text, ‘Sadiq Effendi’. The name Sadiq in Arabic means friend, or companion, and Effendi, a honorific, a learned man worthy of respect. A complicated contraption places a noose around his neck. He appears unafraid and defiant. The final image of Al-Ani’s brilliant filmic installation focuses in on the doomed Effendi’s steely gaze, deeper in until his embossed eyeball, barely a millimetre across in reality, fills the giant screen with its reproachful glare.

Digging in a different direction among the digitised analogue records suggests that rather than marking of the end of the war against Germany & their Ottoman allies, the brass is in fact tracking the events surrounding an early Arab nationalist revolt against the British. That year, 1918, the senior British officer in the city of the holy Shi’a Muslim city of Najaf down the river had been murdered by the rebels in a daring raid on his base, but the region’s mainly Shi’a tribes declined to rise up in support, and the British army moved in to capture them.

Several rebels were hung, the image of ‘Sadiq Effendi’ appearing to represent them all on the brass work. (The tribes did rise up two years later once Britain’s betrayal of T.E. Lawrence’s promise of post-war Arab independence became clear. Then the pilots of RAF biplanes pictured on the plate turned their overwhelming firepower on the Iraqis. Among the flyers was a young Arthur ‘Bomber’ Harris, formulating the deep faith in the effectiveness of terror from the air that characterised his service during WWII as head of RAF Bomber Command.)

The plate itself is on display at the Towner, accompanied by Al-Ani’s perfectly curated selection of works from the Towner’s own collection. The selection references both the circular design and reflective lighting effects of the original brass plate, but also themes of war and airpower. A tiny woodcut by Eric Ravilious is the most connected, a two-dimensional representation of a globe over which flies a warplane, casting its shadow on the world in the form of a deathly cross. Some of Al-Ani’s earlier but complementary films are also on show, shot from drones directly over abandoned British oil refineries and 19th century defences against French invasion.

Jananne Al-Ani Timelines is on show until 22 May 2022. The work was co-commissioned by Film and Video Umbrella and Towner Eastbourne with Art Fund support through the Moving Image Fund for Museums. Presented alongside Bringing to Light: Jananne Al-Ani curates the Towner Collection. Don’t miss.